Malaysia reopens for business with ambitious rakyat-centric digital-first budget

November 9, 2020

Tetration Updates – New capabilities for microsegmentation and workload security

November 11, 2020RDP and the remote desktop

There are two sides to the shift to remote work. On one side, you need to ensure that your people have access to equipment that will allow them to perform their day-to-day tasks. On the other, there needs to be a way to connect back to company resources that will help workers complete those tasks.

One solution to both of these aspects that has proven useful is remote desktop technologies. These technologies allow a user to log into a computer remotely and operate it just as though they were sitting in front of it.

Remote desktop technology is not new and there are a number of solutions available, ranging from platform-independent implementations, such as VNC, to third-party services that make remote desktop connections a breeze to set up and use.

One remote desktop implementation that stands out is Window’s Remote Desktop Services, which relies on the Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) for communication. Being baked into the Windows operating system makes enabling the feature and connecting to it very simple.

RDP as a target

As convenient as this may be, remote desktop solutions—and RDP in particular—come with their share of security concerns. Over the years RDP has been targeted in a variety of ways. Brute-force attacks and login attempts using stolen credentials are a natural concern. The protocol had also suffered its fair share vulnerabilities, allowing for man-in-the-middle attacks and multiple remote code execution vulnerabilities.

The prominence of RDP attacks led the FBI to release an alert about the protocol in late 2018, pointing out that malicious targeting of the protocol was on the rise. The report discussed how malicious actors leveraging ransomware, such as CrySIS and SamSam, were reportedly gaining entry into networks by leveraging poorly configured RDP setups, and even buying and selling stolen RDP credentials on the dark web.

Then, in May 2019, a vulnerability in the way Remote Desktop Services handles RDP requests was disclosed. Dubbed BlueKeep, Microsoft noted that the vulnerability was likely ‘wormable’ and could be used by malware to spread from one unpatched system to another, much like WannaCry had done two years earlier. In the subsequent months two more remote code execution vulnerabilities where discovered in RDP. While no such worm has materialized, RDP had gained significant attention as an avenue into a network.

Frequency of attack

Just how frequently is RDP targeted? It’s a difficult question to answer, simply because of how hard it can be to distinguish malicious from legitimate traffic. Since stolen credentials and brute-force login attempts are often used, unauthorized access will often look like legitimate log-in events.

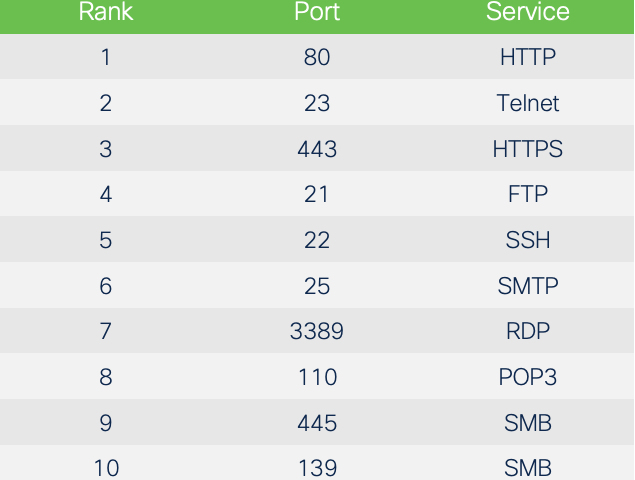

There are a few ways we can qualify the level of RDP attacks. Nmap is a popular network scanning utility that’s often used to check for open ports. The utility includes a list of commonly scanned ports that weights them by how likely they are found to be open. Here are the top 10 TCP ports most likely to be found open, based on Nmap’s current weightings:

RDP ranks seventh overall and is the highest-ranked proprietary port likely to be found open. What is interesting is that only system ports, used by well-known services, come before RDP. The only other proprietary protocol in the list is SMB, the Microsoft file-sharing protocol exploited by WannaCry, which we’ve discussed previously.

Further highlighting concerns about RDP attacks, is the large number of RDP ports that are exposed directly to the Internet. According to data collected from shodan.io, over four million systems that are exposed directly to the internet have TCP port 3389 open.

Of course, just because a port is open doesn’t mean that attackers are regularly targeting it. In order to investigate further, let’s take a look at data from Cisco Secure Endpoint. Here, we’ll specifically look at the exploit prevention technology included, which includes two signatures for detecting BlueKeep attacks.

The first of these signatures will alert when someone scans TCP port 3389 to see if a system is vulnerable to BlueKeep (“CVE-2019-0708 scanning attempt detected”). The second signature alerts when someone attempts to exploit it (“CVE-2019-0708 detected”). We’re using the same methodology in the following chart to arrive at these numbers as we did in the recent Threat Landscape Trends blogs, examining the number of organizations that encountered these signatures each month.

Overall, 31-34 percent of organizations received at least one BlueKeep alert each month in the first half of 2020. What’s interesting is that the type of alert shifted as the year progressed. In January, almost two-thirds of RDP alerts were exploit attempts; by June more than two-thirds were scanning attempts.

On the surface, this appears to indicate that, while attackers may have found initial success in exploiting the port outright earlier in the year, they may have found it more efficient to test if a system was exploitable first. Or it simply worked better in avoiding detection.

One caveat is that within these numbers there will be some alerts triggered by legitimate vulnerability scanners. Such tools are used by security teams to locate vulnerable systems so that they can be addressed. These tools will likely trigger a “scanning attempt detected” signature. In short, not all scanning alerts in the chart above are coming from malicious actors.

Having said that, there are a number of attack frameworks and dual-use tools, such as Metasploit, that have incorporated the BlueKeep exploit. This has significantly lowering the bar for entry when it comes to carrying out successful attacks against RDP enabled systems.

Finally, while around a third of organizations encountered RDP-related alerts each month, the organizations that did were often hammered with alerts. Looking at alerts overall, an incredible proportion of 80-88 percent of exploit alerts picked up by our exploit prevention technology were related to this RDP exploit.

To use or not to use

Perhaps the simplest way to guard against RDP attacks is to not use it. The protocol is disabled in Windows by default, meaning that unless it’s enabled, systems are not susceptible to attack.

If you’re looking for a remote desktop solution, there are a wide variety of less-targeted options available. If cost is an issue, there are even open-source alternatives, such as VNC, that offer similar feature sets.

Nevertheless, any remote desktop solution if compromised through a vulnerability, or by using stolen credentials, gives an attacker a toe hold within an organization through which malicious tools can be installed, or privileges escalated.

Remote desktop access may not be the best solution in the first place. Configuring VPN solutions to allow remote working employees to access to the resources they need not only frees up the network resources that would be used to mirror a desktop environment remotely, but also allows for additional layers of security.

If RDP is necessary, so employees can connect to on-site desktop computers, requiring clients to connect to a VPN first means that clients can be authenticated and scanned to ensure security compliance, plus users can be authenticated by multi-factor authentication, before connecting to RDP.

Understandably, in some organizations that rely on Remote Desktop Services, moving away from RDP may not be an option. In these cases, there are things that can be done to shore up RDP communication.

- Do not connect RDP-enabled systems directly to the internet. Instead, use a VPN and/or proxy connections through a Remote Desktop Gateway.

- Use strong passwords and multi-factor authentication (MFA). Stronger passwords make brute-forcing passwords difficult, while MFA adds a second layer of authentication if a password is stolen.

- Block failed login attempts when they exceed a reasonable number. Apply policies that temporarily block IPs or disable user accounts that do so.

- Change the RDP port. A simple way to avoid blanket scans of the default RDP port is to switch to something other than 3389.

How Cisco Security can help

Cisco’s SecureX platform provides a number of touch points for detecting and blocking RDP-based attacks, which can be viewed within one easy-to-read dashboard.

- Cisco AnyConnect Secure Mobility Client. Using a VPN is one of the easiest and most secure methods for connecting to an organization’s network remotely. AnyConnect simplifies secure access to the company network and provides the security necessary to help keep your organization safe and protected.

- Cisco Secure Access by Duo. Use MFA to verify that RDP connection requests are coming from trusted sources. Duo enables organizations to verify users’ identities before granting access.

- Cisco Secure Firewall can detect and prevent RDP attacks using a number of methods, including Snort rules designed for spotting attacks leveraging the protocol.

- Cisco Secure Endpoint. As described above, Secure Endpoint can detect and block exploit attempts against RDP, as well as block behavioral anomalies often found in RDP attacks.

- Cisco Secure Network Analytics. Whether you use RDP or not, it’s worth monitoring network traffic for policy violations. Network Analytics can assist in detecting anomalies across your networks, flagging applications that should not be used in the environment.