Healthcare organizations are a focus of ransomware attacks

August 10, 2021

Recapping Cisco Secure at Black Hat USA 2021

August 12, 2021Threat Protection: The REvil Ransomware

The REvil ransomware family has been in the news due to its involvement in high-profile incidents, such as the JBS cyberattack and the Kaseya supply chain attack. Yet this threat carries a much more storied history, with varying functionality from one campaign to the next.

The threat actors behind REvil attacks operate under a ransomware-as-a-service model. In this type of setup, affiliates work alongside the REvil developers, using a variety of methods to compromise networks and distribute the ransomware. These affiliates then split the ransom with the threat actors who develop REvil.

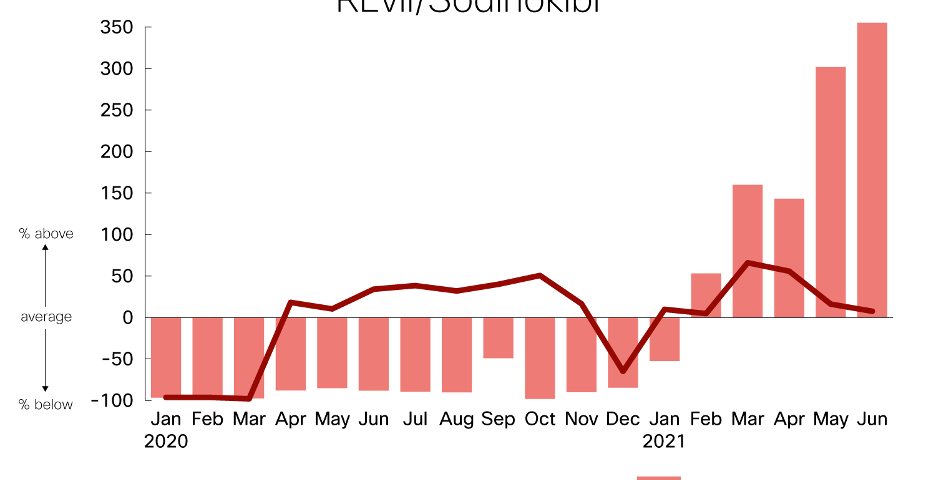

We looked at REvil, also known as Sodinokibi or Sodin, earlier in the year in a Threat Trends blog on DNS Security. In it we talked about how REvil/Sodinokibi compromised far more endpoints than Ryuk, but had far less DNS communication. However, when revisiting these metrics, we noticed that this changed in the beginning of 2021.

What’s interesting in revisiting this data over an 18-month span is that while the number of endpoints didn’t rise dramatically in 2021, comparing each month to the overall averages, the amount of DNS activity did. In fact, the one noticeable drop in endpoints in December appears to coincide with the beginning of a dramatic rise in DNS activity. (For information on the methodology behind this chart, please see the end of the Threat Trends blog.)

What’s notable about the initial attacks is that on many occasions, zero-day vulnerabilities have been leveraged to spread REvil/Sodinokibi. In the most recent case, attackers exploited a zero-day vulnerability in the Kaseya VSA in order to distribute the ransomware. Previously the group exploited the Oracle WebLogic Server vulnerability (CVE-2019-2725) and a Windows privilege escalation vulnerability (CVE-2018-8453) in order to compromise networks and endpoints. There have been reports of other, well-known vulnerabilities being leveraged in campaigns as well.

It’s worth noting that in the case of the campaign that leveraged the Kaseya VSA vulnerability, the threat actors behind REvil disabled the command and control (C2) functionality, among other features, opting to rely on the Kaseya software to deploy and manage the ransomware. This highlights how the malware is frequently tailored to the circumstances, where different features are leveraged from one campaign to the next.

So given how functionality varies, what can REvil/Sodinokibi do on a computer to take control and hold it for ransom? To answer this question, we’ve used Cisco Secure Malware Analytics to look at REvil/Sodinokibi samples. The screenshots that follow showcase various behavioral indicators identified by Secure Malware Analytics when it is executed within a virtualized Windows sandbox.

While the features that follow aren’t present in every REvil/Sodinokibi sample, once it is successfully deployed and launched, the result is generally the same.

What follows provides an overview of how the ransomware goes about locking down a computer to hold it for ransom.

Creating a mutex

One of the first things that REvil/Sodinokibi does is create a mutex. This is a common occurrence with software. Mutexes ensure only one copy of a piece of software can run at a time, avoiding problems that can lead to crashes. However, being a unique identifier for a program, mutexes can sometimes be used to identify malicious activity.

Once the mutex is created, the threat carries out a variety of activities. The functions that follow do not necessarily happen in chronological order—or in one infection—but have been organized into related groupings.

Establishing persistence

As is the case with many threats, REvil/Sodinokibi attempts to embed itself into a computer so it will load when the computer starts. This is often done by creating an “autorun” registry key, which Windows will launch when starting up.

The creation of run keys, like mutexes, is a fairly common practice for software. However, REvil/Sodinokibi sometimes creates run keys that point to files in temporary folders. This sort of behavior is hardly ever done by legitimate programs since files in temporary folders are meant to be just that—temporary.

Terminating processes and services

REvil/Sodinokibi not only establishes persistence, but it also disables and deletes keys associated with processes and services that may interfere with its operation. For example, the following two indicators show it attempting to disable two Windows services: one involved in managing file signatures and certificates, and another that looks after application compatibility.

It’s worth noting that these two behavioral indicators carry a medium threat score. This is because there are legitimate reasons that these activities might happen on a system. For example, processes and services might be disabled by an administrator. However, in this case, REvil/Sodinokibi is clearly removing these processes so that they don’t interfere with the operation of the malicious code.

Deleting backups

Many ransomware threats delete the backups residing on a system that they intend to encrypt. This stops the user from reverting files to previous versions after they’ve been encrypted, taking local file restoration off the table.

Disabling Windows recovery tools

The command that REvil/Sodinokibi uses to delete backups also includes a secondary command that disables access to recovery tools. These tools are available when rebooting a Windows computer, and disabling them further cripples a system, preventing it from easily being restored.

Changing firewall rules

REvil/Sodinokibi sometimes makes changes to the Windows Firewall. In this case, it turns on Network Discovery, which makes it easier to find other computers on the network and spread further.

Contacting the C2 server

To carry out various functions remotely, the threat actors behind REvil often need it to connect back to a C2 server. Each of the C2 servers listed below have been classified as high risk by Cisco Umbrella.

When looking at these domains using Umbrella Investigate, we see that the domain is associated with REvil/Sodinokibi.

Encrypting files

Once most of the previous functions have been carried out, REvil/Sodinokibi will execute its coup de grâce: encrypting the files on the drive.

Creating ransom notes

During this process, REvil/Sodinokibi creates additional files in the folders it encrypts. These files contain information about how to pay the ransom.

Changing desktop wallpaper

Finally, REvil/Sodinokibi changes the desktop wallpaper to draw attention to the fact that the system has been compromised.

The new wallpaper includes a message pointing the user to the ransom file, which contains instructions on how to recover the files on the computer.

Since the files have been successfully encrypted, the computer is now largely unusable. Each file has a file extension that matches what is mentioned in the ransom note (.37n76i in this case).

Defense in the real world

Given the variation in behaviors during infection, running REvil/Sodinokibi samples inside Cisco Secure Malware Analytics is a great way to understand how a particular version of the threat functions. However, when it comes to having security tools in place, it’s unlikely you’ll see this many alerts.

For example, when running Cisco Secure Endpoint, it’s more likely that the REvil/Sodinokibi executable would be detected before it could do any damage.

Protecting against REvil/Sodinokibi and its ilk

On July 13th, the websites and infrastructure associated with the REvil threat actors disappeared from the Internet. Whether the threat will return remains to be seen.

Yet REvil/Sodinokibi is one of many families of ransomware, several of which have been just as active, if not more so. Want to learn more about how ransomware works, as well as ways to protect yourself? Check out the Cisco Secure Ransomware Defense page.

Also be sure to check out our Top Tips for Ransomware Defense for the latest on the machinations behind these threats and further defensive strategies.

Finally, if you’re looking to beef up your ransomware defense and want a simpler and more flexible buying experience, check out our Cisco Secure Choice enterprise agreement.

We’d love to hear what you think. Ask a Question, Comment Below, and Stay Connected with Cisco Secure on social!

Cisco Secure Social Channels

Instagram

Facebook

Twitter

LinkedIn